Jean-Marc Pautras, CFF: “We need to make sure that our voices are heard in Europe”

Jean-Marc Pautras became Director General of the Centre Français des Fonds et Fondations in June 2019 and Treasurer of Dafne in May 2020. With an aim of shining a light on the people behind European philanthropy, we sat down for a conversation. Jean-Marc reveals his youthful aspirations to become a musician, his call for the philanthropy sector to act urgently on climate and why he thinks organised representation of the philanthropy sector is so important. He also shares why philanthropy is the best place for the younger generation to work.

By Dr. Hanna Stähle and Karalyn Gardner

France has demonstrated a very dynamic growth in philanthropic giving over the last decades. What can you tell us about this?

The French foundation sector has gone through different phases throughout history. Two to three hundred years ago, foundations were set up by the Church, the nobility and the wealthy. At this time, there was no public healthcare or education for example, so foundations were established to fill such needs. Many of these very old and large foundations are still active today.

After World War II, there was a growing consideration for social services, such as social security and retirement, which were established in this period. This led to a new generation of funders and foundations. The 1960s and 1970s also witnessed a growth spurt for NGOs and a democratisation of culture which before this was very state-centric.

“This trend continued and the sector has become increasingly institutionalised, culminating with the law “Loi Aillagon” in 2003 which reformed the taxation of philanthropy in France, reducing taxes by 60% for each euro given. This was the Golden Age of philanthropy in France.”

The next step was the structuring of the environment which started with the creation of the Fondation de France in 1969 and, in the 1980s, the establisment of Admical, an association of organisations involved in philanthropy (“mécénat”). This trend continued and the sector has become increasingly institutionalised, culminating with the law “Loi Aillagon” in 2003 which reformed the taxation of philanthropy in France, reducing taxes by 60% for each euro given. This was the Golden Age of philanthropy in France. Since this date, there have been some improvements but the current government has taken decisions which have been less favourable to our sector.

How did you end up working in the foundation sector?

I wanted to be a musician when I was younger. A friend of mine set up a band but, as I was not a good enough musician, I became their manager. At a young age, I was trying to find money to support their music and I realised how difficult this was. I wanted to study and work in a field that supported culture through financial means. Quite quickly, I found “mécénat” (philanthropy) through my studies, and, actually, I wrote my Master’s thesis on this.

After graduating, I worked for Admical as deputy director. These were the best years for French philanthropy. After seven years, I realised that only 5% of public good was financed by private donors and I was interested in the other 95% which why I went to work in the banking sector. All foundations and associations need a bank and many of them take out loans. For fifteen years I worked for a bank specialising in public good, working to support the social economy. My job was to understand the needs of the social economy in terms of financial support and create a response to these needs. The most important lesson that I learned from this time is that there is a lot of money and a lot of need for money. I created a very specialised product that linked associations looking for funding and foundations looking for projects. Also, I realised at that point the importance of umbrella organisations. As a bank wanting to understand how a segment of the economy works, without umbrella organisations, you would need to reach out to each actor individually, which is impossible. Organised representation within the social economy is particularly important as we do not have the economic weight that the private sector can rely on.

“I realised […] the importance of umbrella organisations. As a bank wanting to understand how a segment of the economy works, without umbrella organisations, you would need to reach out to each actor individually, which is impossible.“

What role do you see for philanthropy support organisations at a European level?

The social economy is important for society as a whole, so I believe strongly in the necessity of our sector in France and in Europe. We need to be reinforced and represented collectively to maintain the human values in our society and avoid focusing entirely on profits and products. We need absolutely to be strong. To be strong, we need to work together and enrich ourselves by acknowledging the different perspectives that we bring. We need to make sure that our voices are heard in Europe – by European policy-makers and by all citizens. Collective representation also enables us to participate in discussion at a global level.

How would you describe the specificities of the French philanthropy sector?

“In France, we don’t really speak about the philanthropy sector, we speak about “associations” and “foundations”, which employ almost 10% of the French work force and generate almost 10% of the GDP. The non-profit sector represents 1 930 000 employees and an annual expenditure of roughly 11 billion euros a year.“

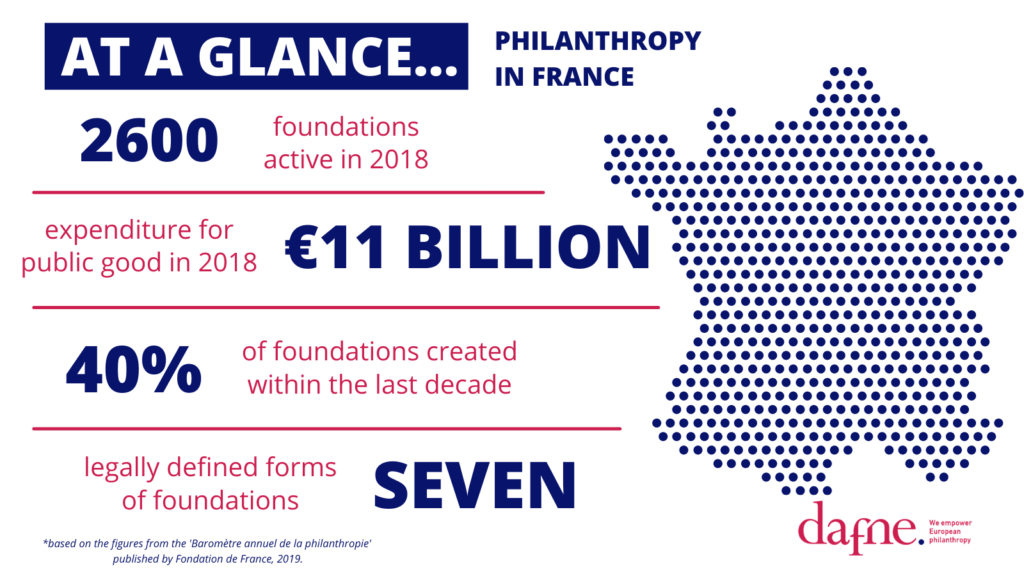

In France, we don’t really speak about the philanthropy sector, we speak about “associations” and foundations””, which employ almost 10% of the French work force and generate almost 10% of the GDP. The non-profit sector represents 1 930 000 employees and an annual expenditure of roughly 11 billion euros a year. Perhaps this represents French philanthropy but, in reality, only 5% of their income is generated from donations, whereas 30-50% of it is provided by public funding. The rest comes from private income such as the delivery of services. In France, we have the concept of “économie sociale et solidaire” (social and supportive economy) which embraces five families of organisations: cooperatives, mutuals, associations, foundations and social enterprises. There is a minister for social economy, there is a public forum for stakeholders and the government to debate, called the “conseil supérieur de l’économie sociale et solidaire,” and there is a private federation, ESS France, of which CFF is a founding member and is represented on its board and executive board.

There is an impressive diversity in the French foundation sector. There are seven legal statutes of foundations in France, which differ greatly from a legal point of view. For example, there are “fondations reconnues d’utilité publique” (public utility foundations); these are oldest form of foundations and are usually quite large. Collectively, their budget amounts to 400.000.000 euros per year. These foundations are quite stable in number and most of their budget comes from public funding. The majority are operational foundations that directly manage their own institutions such as hospitals, social institutions and the like. Three hundred of these foundations which manage direct action, mainly in the fields of social goods, education and culture, represent 70% or 80% of the budget of the foundation sector in France and a similar percentage of employees. The remaining foundations are either fundraising organisations or carry out a combination of fundraising and service provision although often not in their own institutions.

What can you tell us about size and geography of the foundation sector in France?

There are approximately 6000 foundations in France, if we included foundations of all kinds of foundations, especially ‘fonds de dotations.’ (endowment funds). This is a light status for foundations that explains the sharp increase in the number of foundations over the last 15 years. There are almost 3,600 endowment foundations in France but many of these are inactive as when this status was legally introduced, it was possible to create such a foundation without any money. At the time, many organisations created an endowment foundation with no money, but these are still counted in the figures. The numbers on the French foundation sector come from the Fondation de France’s observatory. In June 2020, they published figures from 2018, which found that there were 2,600 active foundations in France, of which 1,650 were active endowment foundations. Two-thirds of foundations are situated in the Ile-de-France region around Paris.

The philanthropic response to Notre Dame fuelled a critical debate on the sector. What issues came up?

The response to the fire in Notre Dame was immense, in a matter of days, hundreds of millions of dollars were raised but the question arose why we could not even raise a few million euros to help people in the streets for example. Also, there was a lot of debate around the tax reduction which only applies to the very wealthy when they give. But this debate was already present in France before the fire, albeit at a lower volume.

What is the position of CFF on this?

We were against this decision and we are still against it. We are asking the government to revise their decision.

In another interview you gave, you said that foundations are not “elderly ladies” but need to foster innovation. What is your take on this?

In 2014, an important law passed that provided a definition of the social economy as well as social innovation. Social innovation was defined as “creating new responses to a social need that is otherwise not covered by the public or private sector.” This was important for our sector because, it demonstrated that foundations have financed such responses, and thus social innovation, for a long time.

Could you give us an example of such innovation?

Endowment foundations financed the “Territoire Zéro Chômeur” (Zero Unemployment Territory) project. These foundations collaborated with associations, receiving the public funding that would have gone directly towards unemployed people, to set up an “entreprise à but d’emploi” (a business with the aim of employment) and offer permanent employment to those who were unemployed. This project was very successful and will be rolled out in the rest of the French territory.

The French government has been in the media recently on account of the involvement of citizens in formulating a climate law which has now been discussed in the French parliamentary assembly. What is your take on this?

This is quite a contentious issue. Before this, the French population was consulted through the Citizens’ Climate Convention. Stakeholders including some foundations, such as the Fondation Nicolas Hulot, told governments not to alter the proposition that came out of the Citzens’ Convention before taking it to the parliamentary assembly. However, the government ignored this recommendation, cutting out and rewriting many of the suggestions from citizens before sending the law proposal to the parliament. Analysis shows that the current proposal will not be enough to reach the goals set out in accordance with the Paris Agreement. This is disappointing.

CFF cannot contribute directly to this process but some of our members, particuarly the Fondation Nicolas Hulot, are closely following any developments. We have a reporting system in the CFFC (the French coalition of foundations on climate) on this matter and we send information on this to our membership.

Why does the philanthropy sector need to take action on the climate crisis?

“If we do not say this together as a sector now, in a short time, governments will impose action through law, donors will stop funding us and journalists will question our intention of providing public good. We need to tackle this issue now to avoids the risks both to the planet and our sectoral reputation.“

Unfortunately, this is the biggest challenge facing the entire planet and it will be for many years to come. We know that this crisis will impact all other aspects of life, for example inequality, culture, food systems and so much more. This will impact all foundations whether their mission centres around education, social issues or culture. Foundations absolutely need to say that they recognise that this subject is urgent and unavoidable. If we do not say this together as a sector now, in a short time, governments will impose action through law, donors will stop funding us and journalists will question our intention of providing public good. We need to tackle this issue now to avoids the risks both to the planet and our sectoral reputation.

What do French foundations need to do? What is your call to action?

Firstly, foundations need to say that the climate crisis is an important subject for them. Secondly, foundations must realise that, regardless of their mission and focus, they can integrate climate into their actions. Try to do better, whatever you are doing – this is my call to action. Thirdly, at CFF, we provide space to share best practices, communicate about the climate crisis and advocate on behalf of the sector.

“Foundations must realise that, regardless of their mission and focus, they can integrate climate into their actions. Try to do better, whatever you are doing – this is my call to action.“

What would your advice be for young people just starting out in the philanthropic sector?

It’s the best place to be! The philanthropic sector allows you to translate your own values and feelings into your job. You could take lots of pleasure from making yoghurt pots or cars, if you want, but I think that creating public good is better than other things. I think it is the best way for you to align your actions and your values.

“The philanthropic sector allows you to translate your own values and feelings into your job.”

You mentioned that when you were younger, you wanted to be a musician. What genre of music did you play?

I was in a rock band. I also used to manage a French rock ‘n’ roll festival, Eurockéennes de Belfort so I used to hear a lot of live music and I love it.

What would the soundtrack of your life be?

Give me another year or two to answer [laughing]… One answer might be Mozart’s Requiem. There is a link between life and death – you have to know what you want to do in life because you know that, eventually, you will die. If you remember that life is short, you go straight to the essence of life. Close contenders would be John Lennon, “Let it Be”. I also love the Tiny Desk Concert version of Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida.”

Do you still play any musical instruments?

The didgeridoo.

Eager to learn more about the philanthropic sector in France? Here is some recommended reading:

- La philanthropie à la Française (rapport remis au premier ministre) 2020

- Legal environment for philanthropy in France 2020, Philanthropy Advocacy

- Le baromètre annuel de la philanthropy 2020, Fondation de France

- Coalition française des fondations pour le climat