Leveraging the work of infrastructure organisations towards regenerative futures

Ad hoc crisis response is overstretching the capacity of many organisations in the non-profit and philanthropic sector that address complex challenges and promote long-term change. This shift is a symptom of larger structural challenges. Due to the dynamics between historical damage, interconnected shocks and the tipping of complex systems, humanity has entered a new era of risk[1]. The related polycrisis[2] is rooted in narratives, models and laws that have disconnected human activity from its biophysical implications for too long. Now, humanity is at a crossroads. Can philanthropy provide direction? If yes, how?

Infrastructure organisations provide capacity building, technical assistance, consulting, workshops, training, conferences, advocacy and research for the non-profit and philanthropic sector[3]. Their work is important in advocating for the rule of law, navigating legal environments, protecting civil society organisations (CSOs) and engaging the public[4]. But most of their objectives are based on the assumption of continuous growth, endless energy supply and abundant natural resources. Blinded by a normalised living beyond planetary boundaries, philanthropy enabled non-profits and CSOs to tackle the negative effects of a massive socio-ecological depletion. To be brutally honest, it helped to optimise an extractive system instead of changing it.

Although scientific knowledge is plentiful, the work towards low-risk decarbonisation and deep societal transition is not advancing at the necessary speed and scope. Nevertheless, most philanthropic practices, portfolios and policies have been energy, material and time blind. In order to leverage the work of infrastructure organisations, biophysical realities, systemic thinking and transformative literacy have to be at the core of any decision making architecture. Intervening in complex systems needs organisational learning and leadership that motivates people to creatively work against the timeline[5].

The upcoming 10×100 days provide an ultimate window of opportunity to adapt current philanthropic practices for an urgent turnaround.

While socio-ecological challenges are growing exponentially, current organisational routines change only incrementally. The next few years provide a crucial moment in human history for responding appropriately to the polycrisis and the end of the carbon pulse[6]. This scientifically backed timeframe has to be understood as a turning point for WHERE philanthropic organisations are heading and HOW they coordinate for systemic shifts. Looking at the entire history of philanthropy, this very decade is THE unique chance to unlock the potential of the sector and enable infrastructure organisations to

- lead by example – engage with uncertainty and dare to shift priorities

- change direction – from minimising destruction to regenerating the future

- coordinate shifts – through cross-sectoral learning for large-scale interventions

Encourage leadership

Engaging with the polycrisis renders predictability and control outdated modi operandi. Linear management approaches suggest predictable outputs but don’t provide a dynamic way for combining crisis response with transformational change. Leadership in an era of persistent emergencies needs mission orientation, open learning and accountable adaptation. The funding metabolism[7] and related decision making processes will only change if single people with leadership responsibilities recognise the interconnectedness of the living world, consider long-term impacts, and invest in distributed systemic shifts. Yes, it’s hard to dare the unknown. Yet being human comes with two special abilities that distinguish us from many other living beings: the way we imagine futures and collaborate at scale. Leading this daring combination will make a massive difference to human development.

Provide direction

Although the concept of sustainability has finally entered the mainstream, it is neither adequate nor executable. Built on the notion that resources are used in a balanced and equitable way for current and future generations, sustainable futures suggest that we only have to minimise negative impacts of human activity on the environment without fundamental shifts i.e. replace fossil cars with electric cars, which is biophysically not feasible. Regeneration[8] goes beyond sustainability and aims to restore and enhance the health and resilience of natural systems. Moving towards regenerative futures includes actively repairing and revitalising damaged or degraded ecosystems, as well as adopting practices that support the rebuilding of natural resources. The consequence of this terminological difference means adapting all philanthropic portfolios immediately.

Coordinate alignment

The fragmentation of funding has been addressed in different ways over the last years. Taking a helicopter view, it might look like dispersed networks of infrastructure organisations are trying to stabilise the status quo rather than strategically linking short-term crisis responses with long-term systemic change. Funding large scale transitions requires coalitions across different interest groups to design transformative pathways into a low-material economy. Developing transformative pathways – matching science with appropriate action – requires all of us to face the biophysical reality of shrinking natural resources and increasing real-world risks. But between commitment and consequential impact lies a significant organisational shift – both internally and across the entire value chain[9]. Approaching these shifts together will make it easier to create new markets, adjust legislation and coordinate for giant leaps.

Rather than watching the breakdown, let’s use each of the next 10×100 days as THE scientifically backed chance to transform by design instead of disaster.

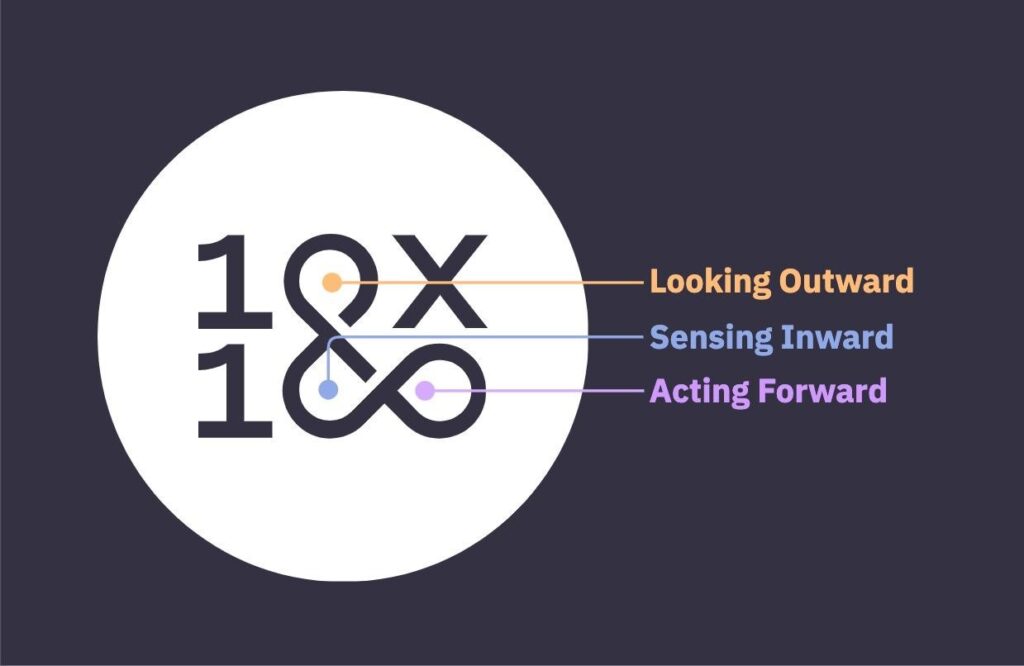

10×100 is an organising mode that provides frequent crisis foresight, practice reflection, strategic gap analysis and the development of appropriate interventions in 10 phases of 100 days. The application of this iterative protocol aims to build transformative capacities by:

- Strengthening the perception of interrelated strategic gaps

- Highlighting the combination of crisis response with systemic change

- Encouraging drastic priority shifts for leaping forward

10×100 formats are self-organised across different contexts, supported by tools and training. Connected to a platform, these elements are able to boost projects, organisations and ecosystems to develop a strategic practice by addressing the next decisive years in tangible timeframes with micro missions and micro commitments.

Picture: 10×100 Core Protocol

Co-create philanthropic shifts

From December 2022 until February 2025, 10×100 operates as a time-bound prototype for a multi-actor learning alliance committed to co-creating an agile organising mode for advancing a just green transition, moving toward net-zero commitments or contributing to SDGs. 10×100 practitioners and supporters are aware of the structural barriers for engaging with the polycrisis and are working towards more drastic measures. Instead of shying away from the complexity of massive collaboration, infrastructure organisations could engage in leveraging each other’s impact by strategically reinforcing it. Until March 2023, we invite lead practitioners and funders to be part of the seed development for the next 100 days. A structured onboarding process will support each partner to clarify their level of commitment, and to develop terms of learning and ways of contributing to a shared accountability.

What is your plan for bridging strategic gaps between the existing knowledge and appropriate action over the next 10×100 decisive days?

Get involved www.10×100.cc

[1] Black R, Busby J, Dabelko GD, de Coning C, Maalim H, Ndiloseh M et al. Environment of Peace: Security in a New Era of Risk. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2022. 98 p. https://doi.org/10.55163/LCLS7037

[2] Tooze, A. (2022). Chartbook #130 Defining polycrisis – from crisis pictures to the crisis matrix. https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-130-defining-polycrisis

[3] WINGS (2019) Impact Case Studies: Promoting an enabling environment for philanthropy and civil society

[4] WINGS (2019). Inspiring Innovations: How infrastructure organizations create thriving civic space https://philanthropyinfocus.org/2019/06/27/inspiring-innovations-how-infrastructure-organizations-create-thriving-civic-space/

[5] IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp.

[6] Hagens, N. & White, DJ (2021). Reality Blind: Integrating the Systems Science Underpinning Our Collective Futures Vol. 1, Independently published https://read.realityblind.world/view/975731937/i/

[7] “Funding metabolism” is used to expand the idea of funding cycle in order to describe the transformation of human imagination into money into social activity and biophysical consequence.

[8] Monbiot, G. (2022). Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet. Penguin Canada

[9] Kite Insights (2022). Every job is a climate job. Why corporate transformation needs climate literacy. https://kiteinsights.com/climate-literacy-corporate-transformation/

Authors