If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail: How to support institutional resilience through Organisational Development

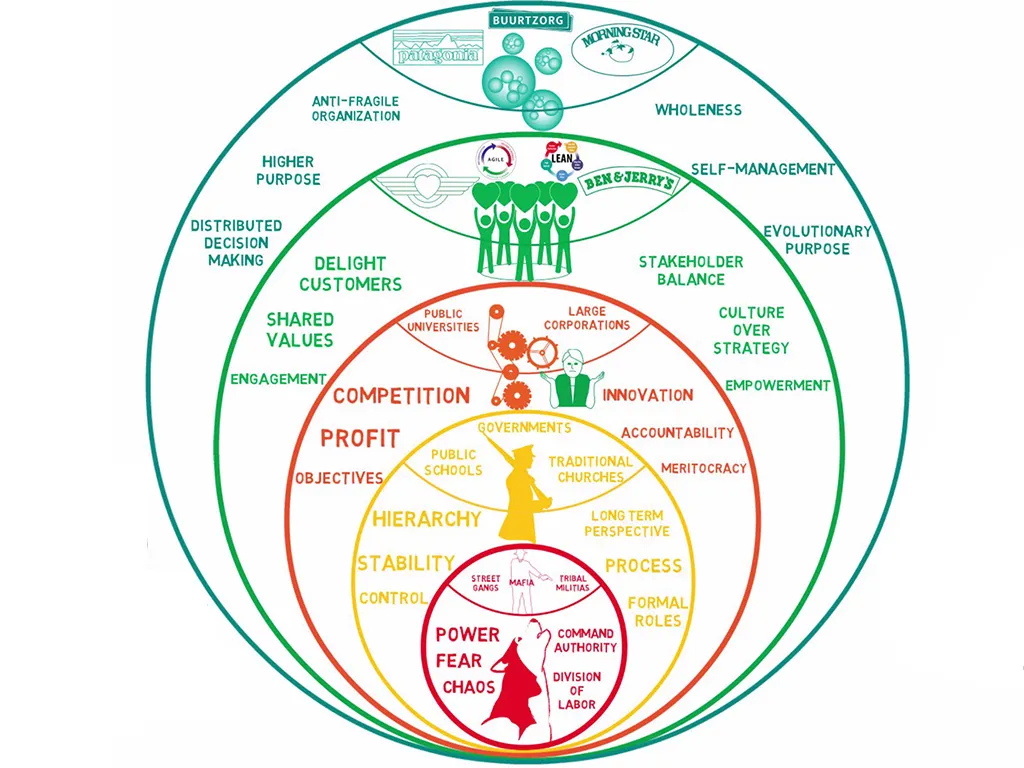

Frederic Laloux’s seminal work, “Reinventing Organizations,” categorises organisational cultures into distinct “colours,” each representing different energies or drivers that shape organisational behaviour. It is an interesting tool for sparking reflections on how organisational culture and organisational development (OD) come together to shape the resilience and effectiveness of partner organisations.

Laloux’s framework allows Organisational Development professionals to gain self-awareness about the dominant energy in their organisation, (ranging between wholeness, empathy, innovation, stability, and competition), and to what extent these energies help to operate as effectively and meaningfully as desired. Indeed, the visual metaphor of colours can help gain understanding about how partners’ organisational cultures both shape and are shaped by their area of work. Take the case of advocacy or humanitarian organisations for example, who tend to harness energies connected to power, accountability, and speed and thus need corresponding organisational structures and investments to support it.

However, there is a risk of transforming a tool meant for inner reflection and self-awareness into a counterproductive diagnostic tool or typology to assess organisational capacity. While a useful reference for a conversation starter, this approach is too simplistic to make funding decisions or design approaches to support partners. Indeed, rather than funding on a diagnosis based on donor-imposed parameters of what is “good enough,” funders should invest in listening and in trust-building to nurture honest and open conversations about how to best support their partners’ work.

Furthermore, when considering this framework in the philanthropy space, certain energies such as competition associated to the colour orange and meritocracy associated to the colour yellow, are more present in funding relationships than empathy and wellness. This brings up important yet challenging conversations about power dynamics between funders and partners, grant-making models that prioritise impact over internal matters and trust-based philanthropy. When donors build relationships with partners on the basis of proving impact and performance monitoring, it stifles openness and transparency around learning, failures, and challenges. This hinders real collaboration between donors and partners and undermines the transformative potential of organisational development.

Perhaps the next step to ponder is the role of Organisational Development in transforming funder and partner relationships to cultivate mutual learning and trust as a precursor to collective impact. Critically, we need to bear in mind the intersection between OD and Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL), because while many funders see MEL as a key area of support for partners, there is also interest in continuing to learn from each other on approaches to measure the effectiveness of providing OD support.

The personalised and relational nature of OD often does not lend itself well to standardised measurement approaches. While MEL practices help answer questions about ‘what,’ OD is more expansive and requires considerations about ‘what,’ ‘how’ and ‘why’ together. Laloux’s colour framing could offer an interesting entry point to redefine an OD impact measurement strategy: what would an organisation’s measurement system that centres wellbeing, empathy, worker autonomy and peer relationships look like? As with the delivery of OD itself, the measurement of partner support requires deep reflection on what tools to use and how these influence funders’ understanding of what a strong and impactful organisation is.

These are challenging yet essential conversations to hold as funders. While the journey towards inner transformation for institutions is not easy, each encounters offers a rich opportunity to critically examine what transformative OD means.

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” was cited by a participant during a recent Organisational Development Community of Practice in-person meeting at The Home of The Human Safety Net in Venice. It proved to be an important framing for subsequent conversations during the workshop, on how to best support the institutional resilience of partners through effective Organisational Development (OD).

Find out more about Philea’s Organisational Development Community of Practice here

Authors