Carola Carazzone, Assifero: “Europe needs a visionary philanthropy sector with engagement and representative power”

“Together, the collective impact we can have is much greater than the sum of our two entities. The reason behind the convergence is to become more effective, more powerful, more visionary, to deliver greater impact and untap the potential of European philanthropy,” says Carola Carazzone, Secretary General of Assifero and Chair of the Dafne Board. In this interview, Carola shares her hopes for the future of the philanthropy sector, her thoughts on the Dafne/EFC convergence process, the experiences that shaped her and her passion for gender equality and social justice. We also discuss philanthropy in Italy, how it reacted to the COVID crisis and the challenges it still needs to overcome.

By Dr. Hanna Stähle and Karalyn Gardner

Where is your head and heart at the moment?

My heart is really in this wonderful opportunity we have as philanthropy support organisations to reshape the philanthropy ecosystem in Europe as a continent, not just the European Union. This is a pivotal moment. Today, more than ever we know the relevance of connectivity, collective leadership, collective impact in tackling the complexity of the challenges in front of us.

What role does European philanthropy infrastructure play in this?

In essence, it is about unlocking the potential of European foundations and funders. Unlocking the intellectual and relational capital that lie in philanthropy is even more crucial than the philanthropic financial and economic capital. Philanthropy infrastructure enlarges the capacities, the competencies, the connections, the credibility of the whole sector.

“Unlocking the intellectual and relational capital that lie in philanthropy is even more crucial than the philanthropic financial and economic capital. Philanthropy infrastructure enlarges the capacities, the competencies, the connections, the credibility of the whole sector.“

Thinking ahead, where do you see the philanthropy sector in ten years?

I see the philanthropy sector recognised not only as a grant-maker or as an actor in terms of financing projects to fill welfare gaps. I see the philanthropy sector seated at the table, able to assess, evaluate, and plan policies for the common good. I see philanthropy as a key stakeholder in the big challenges that lie ahead for Europe: climate, migration, digitalization, inequalities, aging population.

You have been a Dafne Board Member for two years now and we had a wonderful conversation at the time. What has driven you to stand for the position of Dafne Chair?

A lot of humility but also a vision. Humility in terms of serving Dafne – for me this is a true honour. Dafne has been a very meaningful organisation, really forging peer-learning, speeding up the learning process among national associations from Portugal to Russia, from Norway to Turkey. Without Dafne, this process could have taken decades.

In terms of enabling environment for European philanthropy, the ability to represent 10,000 foundations and engaging foundations and funders in a mutually reinforcing cycle at national level and European level, was not a possibility before Dafne. The distinctive, unique value of Dafne is not only representation but also the engagement power that Dafne members can deploy at a national level. The European and national levels nurture each other.

What do you think about the new organisation that we are creating and the Dafne/EFC convergence?

The convergence process between these two organisations is very timely, relevant and significant not only for us, the organisations involved, or the philanthropic sector, but for Europe at large. Europe needs a visionary philanthropy sector with engagement and representative power to really contribute to a more cohesive Europe, a greener Europe, a more sustainable Europe for human development for all people. The collective impact we can have is much greater than the sum of our two entities. The reason behind the convergence is to become more effective, more powerful, more visionary, to deliver greater impact and untap the potential of philanthropy.

“Europe needs a visionary philanthropy sector with engagement and representative power to really contribute to a more cohesive Europe, a greener Europe, a more sustainable Europe for human development for all people.”

How do you envisage your role and mission, as a human rights lawyer and as someone with over 20 years working in the international civil society sector and in philanthropy both in Italy and at the international and European level, as part of ECFI and Ariadne as well as Dafne?

My hope is to give every single day my grain of contribution to social change and to a culture of change-making. Change-making is a humbling concept and very much a participatory process. When you consider yourself a change-maker, someone who plants a seed, you need other people to help this seed flourish. A changemaker is never a single genius or a stand-alone hero. Everyone can be a changemaker. Philanthropy support organisations have a unique role to play; for too long they were considered just networks, something “nice to have.” I like to think of them through the concept of the mycorrhizal network which is alive – our work as philanthropy support organisations is part of the mission, fundamental component of the philanthropic work itself. To meet strategic goals, such as the SDGs, we need philanthropy support organisations to scale up, to enable connectivity and to ensure credibility.

When you think of the new organisation, what values do you consider indispensable?

Inclusion and diversity. Embracing the complexity of the philanthropic sector in Europe and being able to attract and include new forms of philanthropy, the next generation of philanthropists. We need to have a culture of deep and attentive listening so that we feel part of the civil society arena in Europe. Understanding, that, although the philanthropic sector holds capital, we need civil society organisations and social movements to deliver the change that we envision.

“Although the philanthropic sector holds capital, we need civil society organisations and social movements to deliver the change that we envision.”

Independence is very important to me personally and to the Assifero team. We have a serving attitude towards our members because we want to meet each member where they are and we want to support them in their own learning journey, but we also want to have the thoughtful leadership, the gravitas and agency to question, be critical friends and spark critical conversations so that we can help our members to look at themselves in a different way.

For too long, philanthropy was at risk of being solipsistic because of its financial power. Today, we know that nobody nowhere can make a difference in isolation, not even the biggest foundation. We really need to forge more collaboration, strategic partnerships and unusual alliances. We want to play a role not only as a membership organisation but as leadership organisation.

Italy has been severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. How did philanthropy respond to the crisis? What can we learn from this in terms of the role that philanthropy should play in addressing crises?

Philanthropy in Italy was amazing in responding to the emergency, foundations stepped in immediately to react and they really transformed how they offered support to civil society organisations, local authorities, municipalities and hospitals.

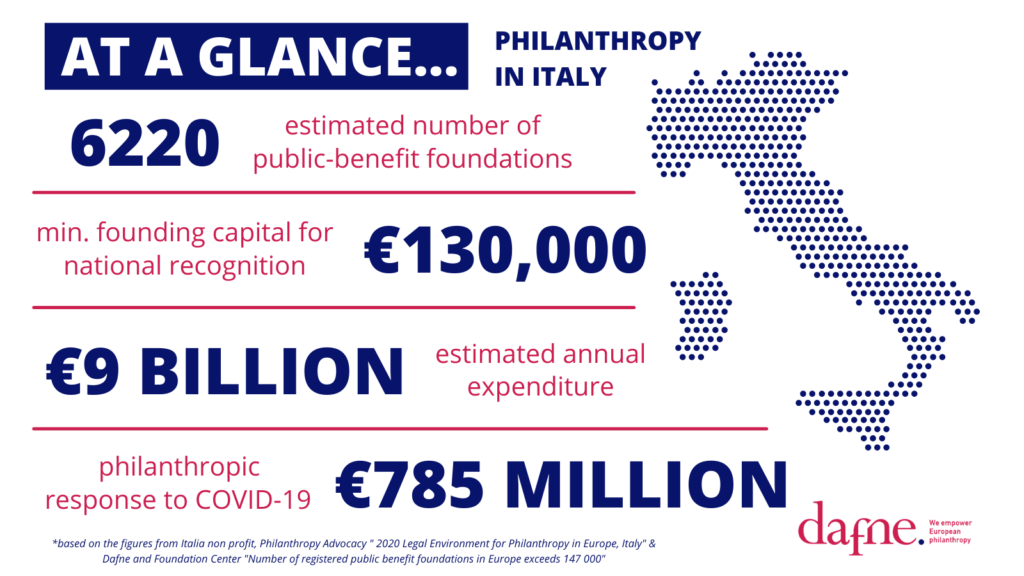

We have mapped 975 initiatives from foundations, enterprises and private donors, who gave over 785 million euros between March and July 2020. This was the first time in our country that we, along with our partner Italia non profit, had carried out a mapping of what happened in terms of deployment of private resources in the face of an emergency. We found that most money went to civil protection, to hospitals or to municipalities to tackle the sanitary emergency and fill the gaps that public services were not able to fill. This was absolutely necessary to protect people.

In the future, I hope that philanthropy can fulfil another role, not only responding and reacting to needs but maximising its unique added value, which includes a long-term vision of intentional change and impact and the freedom to take risks, innovate and experiment in order to find new ways to tackle deep-seated problems, such as inequalities and historically under-served communities. My hope is that philanthropy can become more strategic in the long term in a country that is very much driven by the moment.

“In the future, I hope that philanthropy can fulfil another role, not only responding and reacting to needs but maximising its unique added value, which includes a long-term vision of intentional change and impact and the freedom to take risks, innovate and experiment in order to find new ways to tackle deep-seated problems, such as inequalities and historically under-served communities.”

In a previous interview, you spoke of some cultural constraints that Italian philanthropy faces, what needs to be done to overcome these?

One of the big problems in my country is that we have swung from one extreme to another. In the 80s, public funding was very much given to “family and friends”, it was distributed according to personal relations. In the 90s, as a reaction, everything changed, and funding became bureaucratic and outputs were heavily restricted. For thirty years, this is how the system worked. It is really the depth of the theory of knowledge and practice that we have to change: looking at societal problems in such a linear way, through projects, expected results and lists of micro-activities and fragmented outputs, is unable to capture and embrace today complexity. We need more flexible, enabling approaches, rather than checklists, to tackle in new ways very old and sclerotised problems.

This is reinforced by a lack of trust and a culture of blame avoidance. Public and private donors feel reassured when they issue a call for proposals and give projects-restricted funds because they can avoid taking responsibility for the choice and eventual failure. Everything becomes very bureaucratic and there is a sclerotising burden on grantees because of this blame avoidance culture.

There is also the culture, probably inherited by the Catholic tradition, that the third sector does not have to cost – everything needs to be given to the activities and to the projects with the result that efficiency is correlated with minimal overheads. For thousands of years, social services were carried out in Italy by women for free. For millennia, both nuns and laywomen cared for the sick, people with disabilities, orphans, the whole social sector, for free. This still has consequences and a significant collateral effects including on the professionalism of the sector and on the capacities of the non-profit organisations.

“For thousands of years, social services were carried out in Italy by women for free. […] This still has consequences and a significant collateral effects including on the professionalism of the sector and on the capacities of the non-profit organisations.“

Zooming out to the global level, Italy is hosting the G20 and co-hosting COP26 this year. Is this a window of opportunity for Europe and what role can philanthropy play in this?

So far, philanthropy has not deployed the full extent of its potential in interacting with governments and public institutions, at different levels, through different platforms of multilateralism including the COP, the G20 but also the EU, the Council of Europe, the UN. We can achieve so much more. This is really an opportunity. With Italy hosting the G20, several Italian foundations have joined F20 – Foundations 20 – and there is also a broader strategy of the ASviS- Alleanza Italiana per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile(the Italian multi-stakeholders Alliance for Sustainable Development) which brings together almost 300 organisations among the most important civil society institutions and networks, universities, business sector to collaborate towards the 2030 Agenda.

Together with ASviS, we have a working group of Italian foundations which is producing a position paper and several recommendations for the G20. We will have an event on the 29-30 of September in Milan to bring together Italian foundations on this matter. So, we hope to capitalise on the Italian Presidency of the G20 as an opportunity to show foundations that they can have an impact in the long-term and they can engage with policymakers in a meaningful way to enable a more favourable environment for foundations and for civil society organisations, as well as having a collective impact on specific issues such as climate change.

The way in which you embrace so many issues in such a thoughtful way. How do you do it?

I sometimes envy people with a laser focus, that have spent the last 20 years on a single topic becoming the experts on it. I always have had a broader and overarching view that enables me to look for intersectionality, to try to bridge silos, but it is more superficial. Over the last two decades, I have worked on human rights, international development, social innovation. I have been inspired by Amartya Sen’s work on inequalities, development and freedoms. As a lawyer who specialised in international human rights law, I never wanted to focus on individual judicial cases, but rather on large-scale action-oriented social change programmes. I had the opportunity to be on the Italian non-governmental delegation to Rio in 2012, negotiating the very starting point of the SDGs alongside thousands of other delegates. I love the complex, systemic vision enshrined in the 2030 Agenda.

What is your secret to staying so optimistic? Where do you gain your energy from?

During the lockdown, I re-discovered how much I need contact with nature – the mountains, the forest – to really recharge in nature. I grew up spending long periods in the Alps. Skiing, hiking, camping, trekking from hut to hut, climbing: the Alps taught me concentration, single-mindedness, resilience, endurance, purpose. I find silence in nature and can really listen to my inner being. Once a week, I need to run away and take a walk in the forest. I like to practice yoga, if possible, with someone else. It is very nice to concentrate on breathing. I am also a compulsive reader. I used to enjoy traveling a lot, but I think that this will change. I wake up early and love to have my coffee. I work long hours, but I always try to stop to have a proper lunch, a proper dinner, to take a walk – I try to enjoy the little things and make them count.

Do you have any hidden talents or passions?

Unfortunately, not really. I don’t know exactly how you would say this in English but “scontata” – what you see is what you get. I have no coordination, I am not an artist or a musician, I just love people. I try to spend some time mentoring every week. We have a mentoring scheme through Ariadne, and I try to dedicate a couple of hours a week to younger women in Italy. For example, I was mentoring a group of young women launching the first ever 3-day camp for women working in non-profits in Italy. This was amazing because, in Italy, 70% of employees in the non-profit sector are women but only 20% are in positions of leadership. I love the drive and ownership of these younger women wanting to build up a community of practice around this identity.

“The older I get, the more feminist I become. Twenty years ago, my generation really wanted to demonstrate that we were not feminists, that we were the same as our male counterparts. We had this narrative about meritocracy… but then we had to realise how many unequal opportunities and obstacles create a deeply unequal system.“

I wrote an article in November for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, as I was so disappointed by the reception of the annual report of the European Institute for Gender Equality in Italy. Italy had improved in terms of benchmarking gender equality in a single area, but the media were reporting the improvement in the overall scoring. Upon closer reading, it was clear that this was only because of a single indicator in a single dimension – the number of women on the boards of public companies. There is still so much work to do: we still have segregation in the education system and the job market, gender imbalances at home affect women’s opportunities in the workplace. The older I get, the more feminist I become. Twenty years ago, my generation really wanted to demonstrate that we were not feminists, that we were the same as our male counterparts. We had this narrative about meritocracy… but then we had to realise how many unequal opportunities and obstacles create a deeply unequal system.

Looking back at your career, what would your advice be to your younger self?

Be less shy, dare to be bolder and more confident.

I remember when I was in my late 20s and early 30s, I struggled to speak in public and in working groups as I always had a diminishing attitude and I thought “maybe my thoughts, my contributions aren’t good enough”. But I was only limiting myself. I was educated in a system where women had to listen, not to speak. People asked me why as a teenager I did not study abroad as I was so internationally minded. Although it was possible when I was in high school, I only knew boys who had done this, so it didn’t even cross my mind that this could be a possibility for me. Eventually, I went on an Erasmus year at University when I was in my early 20s, but this is different, and it took me much longer. My younger sister did a year of high school in the US – this was such a lesson to me as the difference between my sister and me because she had the courage to imagine.