Foundations – A Good Deal for Society?

by Katharina Guggi, SwissFoundations

Are foundations a good deal for society?

The reputation of philanthropy is being challenged by perceptions that it is motivated by tax privileges and that this benefit is lost from public purse. Swiss study analyses the costs and benefits of charitable grant-making in Switzerland and yields concrete numbers.

In Switzerland, like in most other European countries, philanthropists are granted tax privileges when setting up foundations. This is based on the conviction that these types of charitable institutions create social added value by generating funds that, otherwise, would not have been used for the common good. To clarify, foundations are only tax-exempt, at least in Switzerland, if they are charitable – i.e. if they promote the common good. Whether this is true is regularly checked and monitored by competent authorities and supervisors.

However, philanthropy has a growing reputation problem and tax breaks play a role in this that’s worthy of considering. In recent news, instances such as Rutger Bregman’s speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos and the intense discussions about the donations pledged in aid of reconstruction after the fire at Notre Dame drew criticism regarding the nature of generosity which often, under scrutiny, errs on the side of hypocrisy. We are increasingly of the opinion that society would be better served if rich individuals were to pay proper taxes instead of distinguishing themselves as ‘generous, good people.’ The revenue generated by these taxes could be used by the state to solve pressing problems more systematically. Can this argument be substantiated?

Swiss study yields concrete numbers

For the first time ever, a Swiss study investigated whether setting up a grant-making foundation pays off for society, or whether the process primarily provides tax breaks which ultimately benefit those who set up the foundation, without generating adequate added value for the public at large. The basis is a comparative mathematical calculation where funds that flow to the general public in the form of donations from a charitable foundation are offset against those which society misses out on by the charitable foundation being exempt from its tax liability.

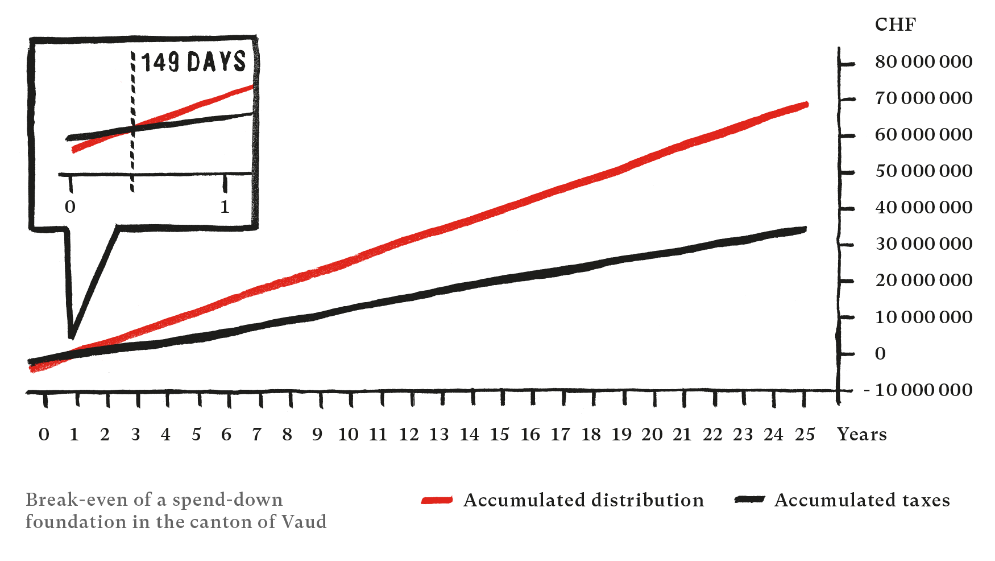

Using an example of CHF 50 million invested in the Anna Dubois environmental foundation, what does this mean in terms of figures? Because Anna is convinced that solutions to environmental issues are urgent, the foundation’s purpose should be implemented as effectively as possible over the next 25 years. For this reason, she set up her foundation as a ‘spend-down’ foundation. Opposite to most traditional ‘endowed’ foundations, not only are the income or return generated on the foundation’s assets, but also the foundation’s assets themselves are used to implement the foundation’s purpose. So, from the capital consumed and returns generated, over a period of 25 years a sum of CHF 69.5 million flows to society in the form of grants.

If Anna Dubois had not set up a foundation and had instead used the CHF 50 million to set up a private investment company, she would have paid taxes of CHF 32.6 million over the same 25 year period. Offsetting this against the CHF 69.5 million in grants from the foundation, this corresponds to an added value of CHF 36.9 million in favour of the foundation solution. From these calculations the study determined that just 149 days after its establishment the funds distributed back into society from the foundation exceeded the regular tax revenues.

A total of four different scenarios were used in the study to calculate the time frame for when a foundation begins to pay off for society. The results are surprisingly clear: in practice, the foundation model breaks even at a point between one month and a maximum of one and a half years after its establishment. From this moment on, the foundation is only financially beneficial for society.

Not all foundations are the same

The calculations speak for themselves and so concrete figures serve as an important basis for a constructive discussion about the added value of foundations. However, the scepticism about philanthropic commitment cannot be substantiated with figures alone. What must be made clear is that the organisational form of a foundation can have an infinite number of different structures. This is clear within the non-profit foundation bubble, but it is also why, when people talk about foundations, they can very easily refer to very different types of organisations. We need a more general understanding of the sector in order to open up the possibilities for further analysis and discussion, and so perhaps it would help to state the obvious a little more.

Furthermore, thanks to recent, highly publicised scandals where it has become clear that some of the money used to set up certain foundations has come from questionable sources, even respectable foundations now struggle with a lack of trust. This only adds to the lack of a solid basis for discussion, which, in many instances, can only be traced back to ignorance and a lack of available information.

The future of foundations: more facts and more voices

So, what information and what facts are necessary in order to be able to have a constructive discussion about the social role of foundations and philanthropic ventures that goes beyond the scope of a tax argument? The need for clear, publicly accessible explanations of what foundations do and how they organise themselves is paramount. People need to know where foundations use their money, and across what sectors they benefit society. We need clarity on the differences between organisations that make grants and other foundations. And we need to be clear on why the concept of ‘non-profit’ is so central when it comes to tax privileges.

To this end, national and international associations such as SwissFoundations and DAFNE are important, but it adds a great deal of credibility when this message comes from the foundations themselves. This is precisely where the initiative for the European Day of Foundations and Donors on 1st October comes in.

When media-covered scandals break the news concerning major international philanthropic figures and foundations, it damages the reputation of charitable foundations in general, even those with unquestionable charitable commitment. In order to maintain favourable conditions that allow philanthropy to work and thrive, all charitable foundations, and especially small, nationally or even regionally active foundations like the one from Anna Dubois, will now be called upon to make a strong case for their own activities.

Arguments, facts and figures can be found in the study “Foundations – A good deal for society”

Inspiration for activities and communication material for the European Day of Foundations and Donors on the 1st October can be found here.

by Katharina Guggi, SwissFoundations

Katharina Guggi holds a master’s degree in Management, Organzation Studies and Cultural Theory and is responsible for Communication and Digital Strategy at SwissFoundations, the association of Swiss grant-making foundations.